—Calvin Luther Martin, PhD

In Part 1, we surveyed Malone’s history and decided (I hope) to stop wringing our hands over the closure of the factories and mills. (They closed all over America, after all. The chances of a town hanging on to its factories in the last 30 years were about as good as the odds of my getting a date with Angelina Jolie.)

State prisons filled the breach. They’ve been an economic boon and life saver.

The only problem being that prisons are a crap shoot; they survive at the caprice of state legislators and governors who, let’s face it, will sooner or later have to make deep cuts to a state budget which is stupendously out of line with state revenues.

If we lose our prisons we’re up the proverbial creek. Alice Hyde could receive a mortal blow, as would all the physicians in town, school budgets, tax base, Walmart, etc.

On the other hand, it’s unlikely we’d lose our prisons outright, wholesale. More realistically, there would be staff cut-backs. Followed a year or so later with more cut-backs. It’s called “death by inches.”

Whether Malone’s prisons die by inches or in one devastating blow or one at a time, like bowling pins, their future is a ticking clock, rather like Cinderella’s fantasy ball. When the hour strikes midnight—which it will inevitably do—Malone, I fear, will turn into a pumpkin.

While the clock ticks, let’s plan for a future we control, not Albany or Washington DC.

Before we rush headlong into brainstorming, we must be clear about what exactly happened to Malone over the last century, since it’s not immediately obvious—till someone points it out. In 1918, when Frederick Seaver published his “Historical Sketches of Franklin County,” state and federal control over Malone was minimal. One hundred years later, we’re practically owned by the state and feds. Today, a mere 15% of Franklin County’s budget comes from taxes. The rest is state and federal money. And that money comes with strings attached. Lots of them.

Unfortunately, none of those strings is going to raise Malone from the (near) dead. They may assist in our revitalization, but no state or federal program is going to redefine and redirect this town—or county, for that matter. That’s up to us.

It’s our job to pick up the pieces from the collapse of the old Malone economy, which arguably ended when Tru-Stitch turned off the lights, and figure out a new Malone economy.

At the moment, Malone’s economy is “public service jobs.” Prisons. Hospital. Clinics. Homeland Security. State Police. Other state jobs. Other government jobs. Schools. Along with a myriad businesses that thrive by servicing all the foregoing agencies and their employees.

The punchline being, we generate very little wealth from our own resources, which traditionally have been farming, manufacturing, lumbering and, at one point, mining. If the state and federal government pulled the plug on Malone, we’d go down the drain.

That thought should be keeping you awake at night. Well, maybe not awake all night. You’re right; Albany and Washington would not pull the plug all at once, though they may do it gradually and selectively. (See “death by inches,” above.)

The point is that we are at the mercy of something that would have appalled Frederick Seaver and his contemporaries at the turn of the 20th century: Malone (and Franklin County) are at the mercy of Big Government. Big Government downstate and Big Government in Washington.

This is another way of saying, Malone is a dependent community. Dependent on Uncle Sam and Uncle Albany. Between them, Uncle Sam and Uncle Albany make the key decisions affecting our fate.

When you add to this formula the powerful corporations (including Wall St. banks) which effectively control the federal & state governments and their agencies, the picture looks even more alarming.

Think of it this way. Think of the Amish who are migrating in considerable numbers to St. Lawrence & Franklin counties. Men, women, and children—just like us. These people have schools. These people go to the doctor and hospital. These people shop at stores. These people make wood products which non-Amish buy. They grow produce which I buy. They do work which we hire them to do. But, mostly, they maintain themselves economically without being owned by Uncle Sam or Uncle Albany.

They are not dependent on Big Government at all.

The Amish community among us is flourishing and noticeably growing. In fact, Amish are buying bankrupt family farms throughout the area and turning them into successful farms.

The question is, How can they do this? One of the reasons they can do it is because they’re not a dependent community—not dependent on Big Government or Big Corporations (or even little corporations). Self-sufficient, in other words.

I know what you’re thinking, “Well, heck, we’re not all gonna become Amish!” And you’re absolutely right. I use the Amish merely to illustrate that “dependency” is a two-edged sword. The biggest difference between you and the Amish family trotting by in their horse & buggy is: these people are largely self-sufficient. And they’re gonna buy your farm when it’s foreclosed. And they’re gonna make it a success.

All by way of saying, Malone (and Franklin County) need to throttle back on the “dependency” model, especially government dependency.

Remember when you learned about slavery when you were in high school, and how it was ended with the passage of the Emancipation Act? Malone needs to start thinking along the lines of “emancipation,” because, ladies & gentlemen, we’re enslaved to Big Government and Big Corporations.

Time to re-read Frederick Seaver and read between the lines. Malone in 1918 was already on the road to dependency. It’s now 2012. We’re now so far down this road, we can scarcely imagine another way of life.

Except, we must imagine the unimaginable. Look at just about everything in our way of life, and realize the common denominator is the word “dependency”:

» Food? Comes to grocery stores from elsewhere. The entire process of producing that food and getting it to Malone is regulated by Big Government.

» Medical care? Entirely dependent on insurance companies and Medicare/Medicaid, both either run by or regulated by Big Government.

» Clothing? Made abroad. Regulated by Big Govt., either here or abroad.

» Appliances? Ditto.

You get the picture. Whenever I propose a new idea for Malone, I inevitably get the response, “Let’s apply for a government grant!” No! That’s dependency! When I need a tree taken down on my street, I call the Dept. of Public Works. Yes, I pay for this service in my taxes, but DPW is indirectly regulated by Big Government—and in having the DPW remove my dead tree, I am simply furthering the “dependency” of my town.

Okay, enough. A moment ago I said, “We’re now so far down this road of dependency, we can scarcely imagine another way of life,” followed by the exhortation, “But we need to!”

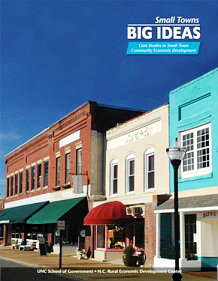

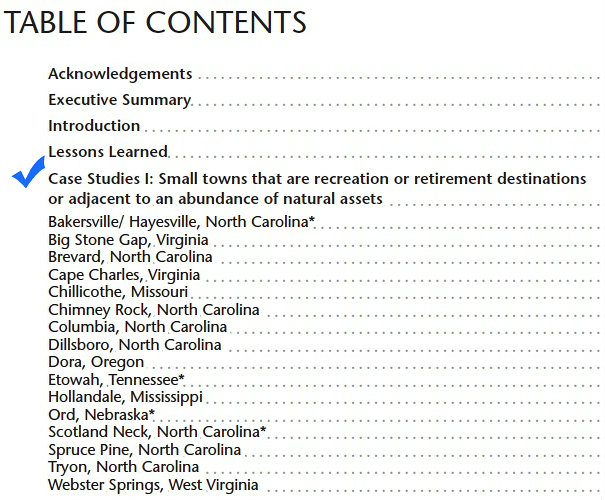

Here’s a start. A study done by the School of Government at the University of North Carolina, called “Small Towns, Big Ideas: Case Studies in Small Town Community Economic Development.” The authors examined 50 small towns across America which were in serious economic distress. Malone could have been one of them. Except, all 50 have managed to pull out of their economic tailspin, with varying degrees of success.

I implore you to read the report. It’s amazing. (It’s also pretty well written.) (Click here for the entire report.)

If you’re a lazy bum like me, and you absolutely won’t read the whole shebang, then please read just the first section, “Case Studies I: Small towns that are recreation or retirement destinations or adjacent to an abundance of natural assets.” This category best fits Malone. In the weeks and months ahead, I will be arguing that Malone should break the back of dependency by turning to its recreation and natural assets.

Meanwhile, read the Executive Summary. “Seven themes emerged from stories in Small Towns, Big Ideas,” write the authors. “These themes are offered as take-away lessons for other communities hoping to learn from small towns with big ideas.” I have excerpted the seven themes, below, focusing on those I feel best address our community.

Before continuing, I must acknowledge Rudy Johnson. Rudy ran for NYS Assembly several years back. He’s a Malone resident. Rudy brought “Small Towns, Big Ideas” to my attention. Thank you, Rudy!

Rudy Johnson & granddaughter

Rudy Johnson & granddaughter

Although they are not shown in quotation marks, the following 7 themes are quoted verbatim from the report:

.

(1) In small towns, community development is economic development.

If community development—compared with economic development—is generally considered to include a broader set of activities aimed at building the capacity of a community, then these case studies demonstrate that capacity-building and other strategies typically associated with community development are analogous with actions designed to produce economic outcomes. . . .

Communities that incorporate economic and broader, longer-term, community development goals stand to gain more than small towns that take a piecemeal approach. . . .

(2) Small towns with the most dramatic outcomes tend to be proactive and future-oriented; they embrace change and assume risk.

These general characteristics of small towns (specifically, of leadership in small towns) perhaps relate to the fact that most communities featured here “hit bottom” and their stories evolved from circumstances in which local folks were willing to try new things and take new risks. . . .

In Chillicothe, Mayor Rodenberg called his core team together on the day the prison announced it was closing. Rather than wasting valuable time, the town initiated an aggressive lobbying campaign and offered an alternative to closure that helped the prison system financially.

Finally, most of the communities profiled in this collection demonstrate a willingness to embrace change and assume risk. For example, Etowah had a history of adapting to shifts in social and economic conditions. Local leaders, therefore, tended to be less steeped in a mindset of “well, this is just the way it’s always been done.” In the face of a growing tourism economy, downtown merchants embraced change and adapted their business models to the shifting circumstances.

(3) Successful community economic development strategies are guided by a broadly held local vision.

Most communities in Small Towns, Big Ideas demonstrate the importance of establishing and maintaining a broadly held vision, including goals for all manner of development activities. . . .

In Ord, Neb., where so much of the momentum comes from one-on-one conversations, local leaders take the time to meet individually with members of the community to ensure that opposition to development efforts does not take root for lack of understanding the larger vision. In terms of maintaining momentum, Douglas, Ga., demonstrates how a local organization (the Chamber of Commerce in this case) can take responsibility for calling stakeholders together on a regular basis to recommit themselves to the community’s vision.

(4) Defining assets and opportunities broadly can yield innovative strategies that capitalize on a community’s competitive advantage.

(5) Innovative local governance, partnerships and organizations significantly enhance the capacity for community economic development.

Most towns featured in Small Towns, Big Ideas include an innovative element of either organization or governance. It is clear that innovative local governance, in a variety of forms, can strengthen a community’s development strategy. In Columbia, N.C., the town’s ability to design an alternative arrangement for generating tax revenues on protected lands helped turn a potential obstacle into a local innovation. In Selma, N.C., the town used an innovative property tax incentive tool to focus redevelopment on a blighted area of town. . . .

(6) Effective communities identify, measure and celebrate short-term successes to sustain support for long-term community economic development.

Given the long-term nature of community development, and the fact that measurable results from a particular project may be decades in the making, leaders in small towns must repeatedly make the case for the importance of their efforts. Making the case is important to maintain momentum, invigorate volunteers and donors, convince skeptics and, most importantly, keep the focus on the vision or the goals established in a community’s strategic plan. Many of the communities profiled in this study recognize that making the case is an ongoing and continuous effort and that there are a number of strategies for doing it.

First, short-term success can build long-term momentum. Obviously, the best way to make the case for any intervention is to demonstrate success. Along these lines, Scotland Neck, N.C., began with actions that would demonstrate success quickly. Town leaders decided to support local hunting and fishing guides, to start bringing more tourists into town and to show local residents that there was reason to be optimistic. This initial success helped them build momentum before beginning to tackle more intractable challenges.

Similarly, to maintain buy-in from the Arkansas community, the initial action steps in Helena’s strategic plan were those that could be accomplished in short order and for which there was already some momentum.

By starting with “low-hanging fruit,” town leaders demonstrated that change was possible. Once people started seeing change happen, there was more of an incentive to join in the process. Short-term success is a means for making the case that particular community economic development activities are worth the investment.

(7) Viable community economic development involves the use of a comprehensive package of strategies and tools, rather than a piecemeal approach.

The capstone lesson is, perhaps, a reaffirmation of a point that we have heard over and over again: there is no silver bullet. No single strategy saved any community in this study. Successful development in small towns is always multifaceted. Small towns should take nothing off the table in selecting strategies to pursue. Successful communities tend to have evolved to the point where they have a comprehensive package of strategies and tools that are aligned with the core assets, challenges and opportunities within their regional context.

.

In closing, I’d like to underscore these 3 points:

(a) “Successful development in small towns is always multifaceted.”

(b) “There is no silver bullet.”

(c) And, my favorite, “Small towns should take nothing off the table in selecting strategies to pursue.”

Let’s say Malone succeeds and joins these 50 towns as a “success story.” There still will be dependency; we ain’t gonna be living like the Amish. But—here’s the good news—we won’t be as dependent on Big Government as we are today, and, if we do it right, we will have begun the journey toward self-sufficiency.

I end with a small story. Do you know how Franklin Academy got built? Read Seaver’s “History”; it’s all in there. (Click here for the relevant pages.) But I’ll tell you how it got built, ’cause it’s such a fabulous story. It was not through a grant. It was not with state or federal funding. It was not from a big financial donation. It was not by raising taxes.

As already shown, provision was made almost at once upon the erection of the town [Malone] for educational facilities of a higher order than the common schools afforded, though the institution then established had more of a private than a public character. It was, therefore, not altogether satisfying. The requirements for an academic charter in 1811 had been merely that an institution have an assured annual income of a hundred dollars, but the people were too poor to provide even that paltry sum, and the effort to gain the Regents’ sanction had to be given over temporarily.

In 1823, however, agitation began in earnest to secure an academy which should be in fact a public institution, and all that the name implies. Again unsuccessful for a time because of inability to satisfy the Board of Regents that adequate pledges were in hand for a building and for maintenance—the requirements in this regard having been increased to two hundred and fifty dollars a year—a later movement (begun in 1827 and prosecuted more or less vigorously for several years) resulted in 1831 in securing the necessary funds, and a charter was granted April 28th of that year—not for the Harison institution, however, but for a new establishment to be known as Franklin Academy.

The scheme employed for procuring funds is noteworthy. Seventy-three men executed mortgages on their homes and farms conditioned for the payment of interest at seven per cent on the amount of the respective obligations so given. The largest principal sum pledged was only $225, and the smallest $15. Some were for odd amounts, one having been for $21.49, which meant that the mortgagor should pay $1.50 per year.

All of the mortgages had a life of twenty years, at the end of which period contributions under them were to cease, and the instruments be discharged.

Scarcely any money was in circulation at the time, and few men in the community had assured cash incomes even for taxes and other imperative requirements, so that the men who engaged to pay even a small amount secured by mortgage dreaded lest he be compelled to default, with consequent loss of his property. It may thus be realized that in signing, all except those who were the most prosperous did so hesitatingly and with trepidation.

Nevertheless public spirit and self-sacrifice triumphed, and the proposed institution was guaranteed an annual income of a trifle under three hundred dollars.

Franklin Academy thus came into existence, and for more than three quarters of a century has been doing beneficent work of value beyond all calculation (pp. 420-21).